Harrison Race Riots

Though nowhere near as murderous as other race riots across the state, the Harrison Race Riots of 1905 and 1909 drove all but one African American from Harrison (Boone County), creating by violence an all-white community similar to other such “sundown towns” in northern and western Arkansas. With the headquarters of the Arkansas Faction of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) located nearby, Harrison has retained the legacy of its ethnic cleansing through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

Though nowhere near as murderous as other race riots across the state, the Harrison Race Riots of 1905 and 1909 drove all but one African American from Harrison (Boone County), creating by violence an all-white community similar to other such “sundown towns” in northern and western Arkansas. With the headquarters of the Arkansas Faction of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) located nearby, Harrison has retained the legacy of its ethnic cleansing through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

The U.S. Census of 1900 revealed a black community in Harrison of 115 people out of 1,501 residents. This constituted a vibrant community that, despite its poverty, had a cohesive culture and deep roots. By all accounts, relations between the white and black communities were relatively friendly and stable before the riots (dependent, of course, upon the expected subservience of black citizens to white people). The catalyst for change was the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad (later the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad), which was built through Harrison in 1901, exciting the populace with visions of prosperity. But the railroad went bankrupt on July 1, 1905, creating hardship for the townsfolk and the railroad workers who had moved to the area. The completion of the rival Missouri Pacific line, which ran through Omaha (Boone County), fifteen miles north of Harrison, left many more unemployed, both black and white. Some found their way into Harrison, where their lack of deference (they had been independent and used to being paid well for their work) enflamed the ire of Harrison’s white residents.

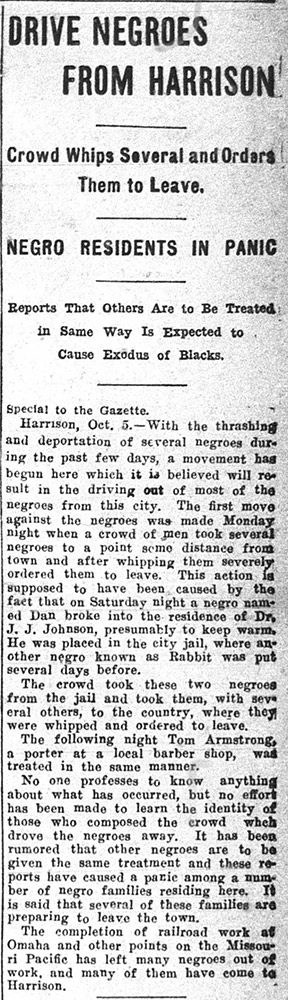

The enmity that Harrison felt for its black population came to a head on October 2, 1905, when a white mob stormed the jail and took two black prisoners—one of whom had been charged two days earlier with breaking into Dr. John J. Johnson’s residence—along with several others and transported them outside city limits. There, they whipped their captives and ordered them to leave. The mob then went on a rampage through Harrison’s black community. Numbering about thirty, they burned down homes, shot out windows, and ordered all African Americans to vacate the town that night. Many did, fleeing to places such as Fayetteville (Washington County) and Eureka Springs (Carroll County) or to Missouri. In the following days, the people who had stayed were attacked and harassed. On October 7, 1905, J. E. Hibdon, member of a posse, shot and killed black railroad worker George Richards at the Omaha railroad camp.

The civic power structure of Harrison likely approved of the mob action. According to Jacqueline Froelich and David Zimmerman, “Diligent research has failed to reveal any records of actions taken by law enforcement officers or any other local officials to protect Harrison’s African American community at any time preceding, during, or after the attacks.” But John Henry Rogers and James Kent Barnes—judge of the Western District of Arkansas and district attorney, respectively—sought to use a grand jury already scheduled to be impaneled to bring the perpetrators of mob violence to justice. Their task was rendered impossible by the disappearance of so many potential black witnesses and by the reluctance of the white jury to seek indictments against their fellow men, many of whom were reputedly of good standing in the community.

The remnants of the black community in Harrison lived a tenuous existence until 1909, when Harrison’s transformation into an all-white town was made complete by yet another riot. The ostensible catalyst for this second round of violence was the January 18, 1909, arrest of Charles Stinnett on the charge of raping a white woman. To stem the potential for mob violence, Judge B. B. Hudgins made provisions for a speedy trial. On January 21, Stinnett and the victim, Emma Lovett, testified, and the jury went into closed session at 11:00 a.m. to return a guilty verdict four hours later, with a sentence of death by hanging.

Upon hearing news that Lovett was gravely ill after the trial, a lynch mob formed and proceeded toward the Harrison jail; Stinnett was transported to Marshall (Searcy County). But the continuing presence of the mob resulted in another mass exodus of black citizens from Harrison. Most left on the night of January 28, 1909, following some of the same roads their predecessors took four years earlier. Only one black townsperson, Alecta Caledonia Melvina Smith, known as “Aunt Vine,” remained. The property of those who left was quickly declared forfeit.

Racial violence in Boone County may have led African Americans in neighboring counties to flee the area. Census records for Carroll and Madison counties show that, between 1900 and 1910, the black population dropped steeply. Whether this was because of a desire to escape the area’s climate of hostility, or whether other, unreported incidents of racial violence may have driven the black population out, remains unknown.

Contents courtesy of The Encyclopedia Of Arkansas